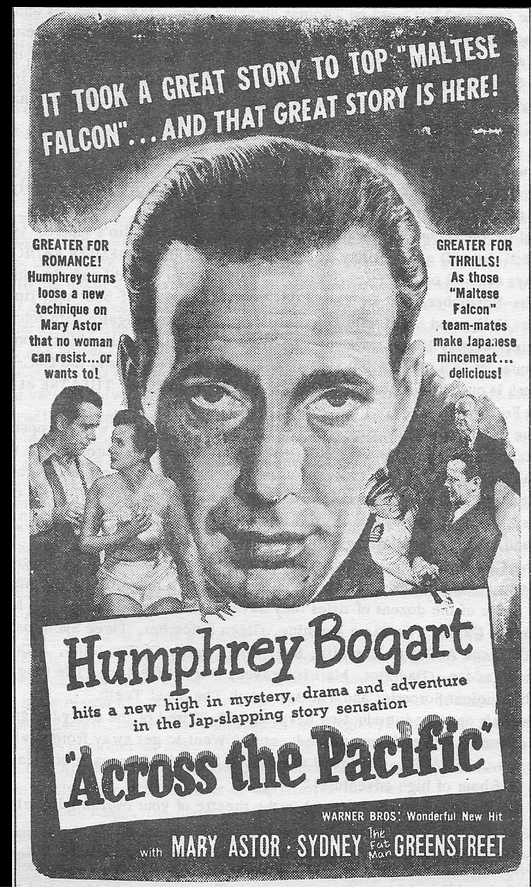

The Maltese Falcon (1941), Across the Pacific (1942), and Casablanca (a little later in 1942) make up a trio of films that interlock in complicated ways.

All three: star Humphrey Bogart, costar Sidney Greenstreet, released by Warner Brothers.

Falcon and Pacific: directed by John Huston, costar Mary Astor (whom the Bogie character calls “Angel”), Greenstreet character referred to as “the Fat Man.” (He’s even called that in the Across the Pacific newspaper ad, above.)

Falcon and Casablanca: costar Peter Lorre.

Pacific and Casablanca: Bogart character named “Rick,” film is set in the days just before Pearl Harbor.

Across the Pacific is the weakest of the three, but it’s the only one with a movie-in-movie scene, and hence it’s my subject today. Bogart is Rick Leland, who, as the movie opens, has been court-martialed from the U.S. Army for stealing. But things are not as they seem. He’s actually a spy on a top-secret mission, which involves him traveling on a Japanese ship from Nova Scotia to Yokahama. But the ship is held up in Panama, where the denouement takes place.

The whole thing is pretty ludicrous, not to mention racist. Rick at one point actually says, “They all look alike.” (Huston and Warner Brothers must have thought so, too: all the Japanese characters are played by people of Chinese descent. In 1942, of course, Japanese-Americans were otherwise engaged in internment camps.)

But by the time, the movie-in-movie scene comes around, all the plot points have been taken care of and we can get down to action. Rick’s contact has told him to go to a movie house, which turns out to service Panama’s apparently sizeable Japanese community. Rick sits down, and Huston very skillfully builds suspense that suddenly erupts in a climax reminiscent of HItchock’s Saboteur, which had come out just a few months earlier. Note the audio track, with its mix of audience titters, a crying baby, and the movie’s dialogue and soundtrack.

Now, you will have noticed the question mark in the title of this post. The usually reliable IMDB doesn’t name the film being shown, and I haven’t been able to find it in any other source. I happen to have a neighbor and occasional tennis partner named Satoru Saito, who is a professor of Japanese literature and film at Rutgers University. He was kind enough to take a look at the clip and reported:

“Unfortunately, I couldn’t figure out the name of the film. The poster in the lobby (the same one as the outside) is a women’s magazine (Fujin koron) cover. As for what the characters are saying, it’s a bit hard because the woman is definitely not a Japanese speaker, and they are both reading off a script (the movie is likely a silent film, and I don’t know if what is being said accurately reflects the silent movie). The dialogue is something like this:

The man: “I will make sure to use my time only for you. I won’t go out with Hanako. For ___ reason, I couldn’t help it.”

Woman: “I am happy to hear that…. Oh my classmates are here.”

Classmates: “They are very touchy.”

Man: “You must be tired; let’s go for some tea.”

Woman: “I don’t think I can today.”

Man: “Don’t say that, let’s go.”

So that’s all I got. If anybody has a clue to what this movie is, I would be delighted to hear it.