Home Alone (1990; directed by Chris Columbus; conceived, written and produced by John Hughes) presses all the buttons. You’ve got your madcap humor, your cartoon violence, your patented John Hughes pathos, your upper-middle-class white Midwestern suburbanite setting, and (possibly the only element that still feels fresh and unpremeditated) your breakout performance by Macaulay Culkin as 8-year-old Kevin, who (it can’t be a spoiler if it’s the title of the movie) is inadvertently left home alone when his family flies to Paris for Christmas.

Ah yes, Christmas — that’s the other big button. Home Alone was conceived in and dedicated to the proposition of being a holiday movie. One way it establishes this is time-honored: having characters watch (on TV) Miracle on 34th Street, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and of course It’s a Wonderful Life. (The last is seen by the Kevin-less clan while in Paris, and is dubbed into French.)

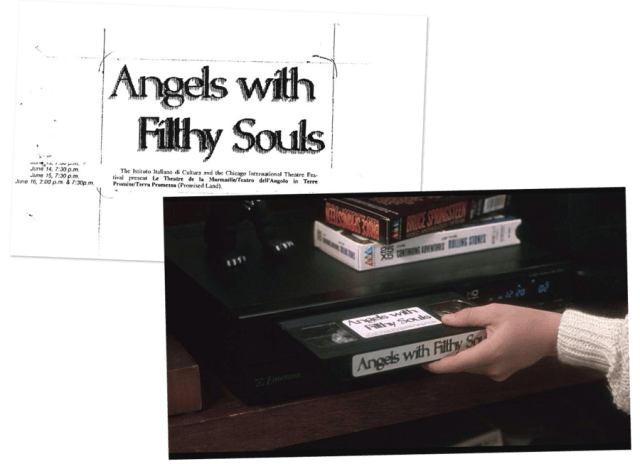

There’s one other movie that’s featured in the film: Angels with Filthy Souls. Kevin finds a VHS tape of it and, presumably titillated by the title, slips it into the VCR. (It sure beats the the other choices on top of the player, the boomer rock of Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones.)

He and the audience see what appears to be a 1930s film noir, in black and white of course. A trench-coated guy named Snakes, who has a very gangster look to him, pays a call on a private eye named Johnny. (Even if we couldn’t backwards-read the words “Private Investigator” on his frosted-glass door, we could tell his occupation by the frosted-glass door itself.) There’s something odd about the clip, however. For one thing, Johnny has a really strong Chicago accent, not something often heard in movies; just listen to the way he says, “He’s upstairs, taking a bey-uth.” For another, Angels with Filthy Souls sounds just a little too over-the-top to be the title of a sequel to the real ’30s movie Angels with Dirty Faces. And finally, the shoot-him-full-of-lead sadistic violence, followed by the gleeful catchphrase-to-be, “Keep the change, ya filthy animal,” would in no way have passed muster with the Hollywood Hays office at the time.

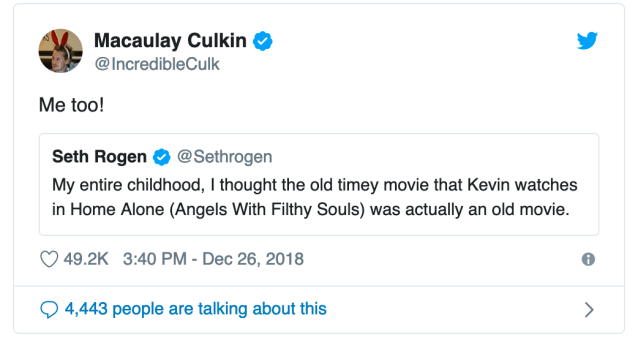

Nevertheless, some people persisted for a long time in believing Angels with Dirty Souls was a real movie–including Seth Rogen, Chris Evans, and Nick Kroll.

And also including Macaulay Culkin!

I’m not sure what disabused Rogen of his error, but he would have known the truth had he read a 2015 Vanity Fair article that told the whole story of the conception and production of Angels, down to the care taken to recreate the noir look. Director of Photography Julio Macat

persuaded Columbus to shoot the sequence using the techniques and black-and-white negative film stock of movies from the 40s. The high-key lighting, high-contrast aesthetic would evoke “a cross between film noir and the really crazy stuff you see in early television, like Playhouse 90 or One Step Beyond,” said production designer John Muto.

Like most of the other interior shots in Home Alone, including all the scenes inside the McCallister family home, the sequence was shot on a sound stage in the abandoned New Trier West High School gymnasium. The entire set consisted of just a couple of walls. (Webster suspects that the walls were reused in the “real world” of the movie, for the set of the police office. “We didn’t have the biggest construction budget.”)

Johnny’s office was designed especially for maximum dramatic backlighting potential: pebbly-textured translucent glass on the door and a Palladian window that would sinisterly spotlight him at his desk through Venetian blinds.

As I suggested earlier, Home Alone is a well-oiled machine, and of course, true to the principle of Chekhov’s gun, Angels with Dirty Souls shows up again, and again, used by Kevin as part of his whole-house booby trap strategy. The second time, he’s trying to foil the inept crook Marv (Daniel Stern).

Hughes and Columbus were not done with Angels with Filthy Souls. Its sequel — Angels with Even Filthier Souls — shows up in their 1992 sequel, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, and repetitively is used to scare the officious concierge at the Plaza Hotel (Tim Curry).

Merry Christmas, ya filthy animals.

The Apartment, which won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay (by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond), was presented as a comedy that mocked romantic mores and man-in-the-gray-flannel-suit corporate culture, with its notorious attachment to the suffix “-wise.” But removed from its turn-of-the-decade context, and especially viewed in the light of the Me-Too movement, the film is chilling.

The Apartment, which won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay (by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond), was presented as a comedy that mocked romantic mores and man-in-the-gray-flannel-suit corporate culture, with its notorious attachment to the suffix “-wise.” But removed from its turn-of-the-decade context, and especially viewed in the light of the Me-Too movement, the film is chilling.